The Great Tomato Caper of ’72

Now, I don’t like to boast — mainly because it takes energy, and I’ve misplaced most of mine — but I will say this much: in the summer of 1972, I became the first man in Piedmont history to declare war on a tomato thief and lose twice.

See, I had a garden then. Not just any garden, mind you — the finest stretch of soil this side of the railroad tracks. Rows of tomatoes, neat as choirboys. Planted ‘em myself, tended ‘em daily, and named the best ones after country singers I admired. There was Loretta, Tammy, Conway, and a big, beautiful beefsteak I called Elvis, because he drew a crowd.

Now, every morning I’d go out, whistle a little tune, and count my crop. Then one morning, I noticed something scandalous: Elvis had left the building.

Gone. Plucked clean off the vine, stem dangling like a loose tooth.

At first, I suspected my neighbor, Harold Dunn. He’s the kind of man who’d borrow your shovel, forget to return it, and then blame you for stealing it when he finds it in his own shed. But Harold’s too lazy to commit a crime that involves bending over.

So I figured it must be an animal. A raccoon, perhaps, or a particularly ambitious squirrel. I sprinkled cayenne pepper, hung wind chimes, even installed one of those plastic owls. It didn’t help. By the next week, Loretta and Conway were gone too.

Now I was mad. A man can overlook theft, but he cannot abide insult. I decided to take matters into my own hands.

I borrowed my nephew’s camping lantern and stayed up half the night, sitting behind the rain barrel in my bathrobe and slippers, armed with nothing but a garden trowel and righteous fury.

Sometime around two a.m., I heard rustling. Then a shape moved between the vines. It was low, quick, and sneaky. I raised the lantern and hollered, “Who goes there?”

There came a squeal, a crash, and the unmistakable sound of Harold Dunn’s overalls ripping.

Turns out Harold had been sneaking into my garden under cover of darkness to “sample the produce,” which is his way of saying steal tomatoes and lie about it later.

He claimed he thought the garden was “communal,” which is what folks in Piedmont call something they want but don’t own. I told him I’d call the law, but then I remembered the law was his cousin. So I settled for dignity.

Or tried to.

Because just as I was giving him a piece of my mind, the lantern tipped, the rain barrel rolled, and the two of us ended up sprawled in the mud, fighting over a single tomato that wasn’t even ripe.

It was a draw. The tomato burst. The war ended in a splatter of pulp and pride.

By morning, the whole town knew. Miss Lurleen Cobb (who, if gossip were an Olympic sport, would’ve retired with a gold medal and her own parade) told it at the Huddle House before breakfast.

So now, whenever folks pass my house and see my garden, they smile and say, “How’s the crop this year, Toad? Lost any prisoners lately?”

And I smile right back, because I learned something that summer: in Piedmont, it’s not the tomato that matters — it’s the telling.

Besides, I started growing okra after that. Ain’t nobody ever stolen okra twice.

*****

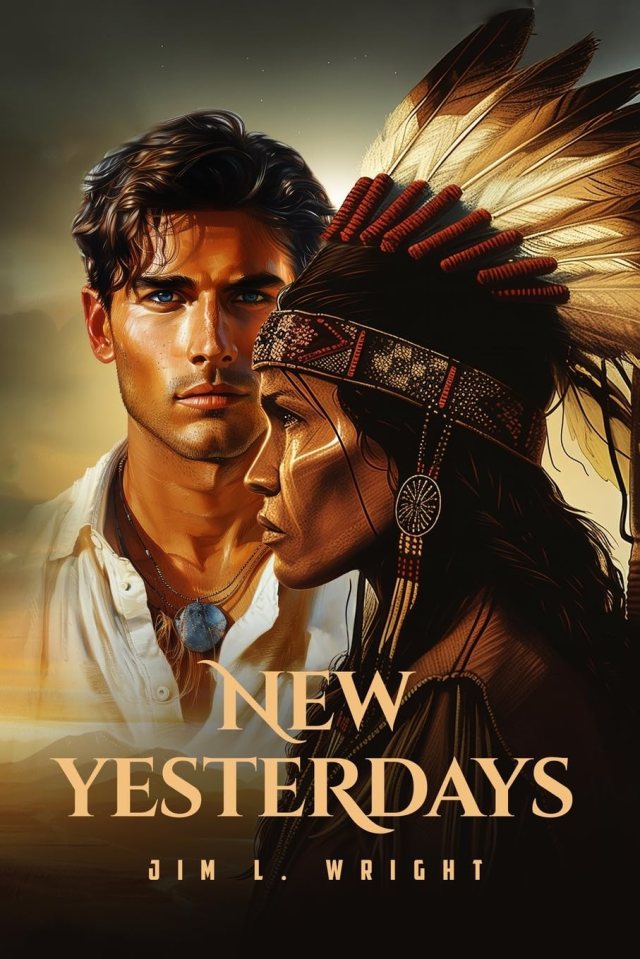

New Yesterdays is available through the following links: Books-A-Million, Barnes & Noble, and Amazon as well as your favorite bookshops. The Audiobook is available from Libro.fm, as well as Amazon.