Now, I reckon most folks would tell you a story about such a matter with a heap of thunder and tragedy, and Lord knows there’s enough of that to go around. But the human heart, well, it’s a contrary beast. It don’t always listen to kings or generals or the grand notions of destiny. It goes on beating its own simple rhythm, like a drum in the deep woods, and a man’s got to march to it, even if the whole world is marching the other way.

What I have here is a bundle of letters, saved from the fire and the flood, and they tell a truer tale of this land than any in the schoolbooks. They passed between two fellers—one named Elias, who came from a line of Alabama farmers, and the other, a Cherokee man called Awi Usdi, or Little Deer.

The first is from Elias, carved on a piece of birch bark and left in a hollow oak.

Awi Usdi,

I write this not knowing if you’ll find it, or if you’ll laugh at the foolishness of a white man scratching on a tree. I saw you again today, down by the Coosa. You were standing so still, watching the water, you might have been a sycamore yourself. I was supposed to be checking my trapline, but I found myself just watching you. It’s a peculiar thing. My Pa talks of “Manifest Destiny” and the great march of our people westward, and all the while, my own destiny seems to have gotten itself manifestly tangled, standing stock-still on a riverbank, watching a man who is not of my people, and feeling more kinship with him than any soul in our meeting house.

This land is full of shouting. But you are quiet. And in that quiet, I hear something I’ve been hungry for all my life.

Your fool,

Elias

The reply, left in the same spot, was written in a fine, steady hand on traded paper.

Elias,

Do not mistake stillness for peace. The river you see as calm on the surface runs deep and fast beneath. My people know this. We have learned to listen to the world and to men. I have seen you, too, watching. Your kind marches across the land like a summer storm, loud and sure of its right to be there. You are not like them. There is a silence in you, too—a different kind. A listening silence.

They are drawing new lines on the maps their God drew for them at the beginning. They do not see the old lines, the ones drawn by the rivers and the deer trails. Your lines are made of ink. Ours are made of song. How can two such worlds ever meet?

And yet.

Awi Usdi

A year later, the tone had changed. The pressure was building.

My Dear Awi,

The talk in town is ugly. They speak of President Jackson’s plan, of “removal.” They use words like “voluntary” and “for their own good,” but their eyes are hard when they say it. When they speak of your people, I feel a heat in my blood that shames me. These are my neighbors; the men I break bread with. They are good men who love their children and say their prayers. How can good men speak of such things with such easy hearts?

I look at the land they say we are destined to own, and all I can think is that I am destined to lose the only thing in it that feels like home to me. You.

I am afraid.

Elias

The reply was swift and written on a scrap of hide.

Elias,

Do not be afraid for me. Be afraid for them. A man who can convince himself he is doing wrong for a greater good is a man who has lost his way in a deep wood with no stars to guide him. My father says the white man’s hunger is a bottomless pit. He says we will be taken west, to a place beyond the Great River, a place they have not spoiled because they have not yet found a use for it.

This is not about land. It is about a story. Their story says the land is empty, waiting for them. Our story says it is full, has always been full—full of life, of memory, of spirit. They cannot bear our story, for if it is true, then their story is a lie. So, they must rub us out, like a mark on their map.

But they cannot map the heart. Where I go, you will be with me.

Awi Usdi

The final letter, smudged and carried by a nervous hand, was from Elias.

Awi,

It is done. The soldiers are here. They are rounding up everyone. It is not an argument anymore; it is a fact. A terrible, simple fact, like a rock or a rifle. They call it “The Trail of Tears.” I have heard the words. I have seen the faces.

I have a horse and a rifle. I know the back ways. Meet me at the high falls. We will go. West, east, north—I don’t care. We will find a place where their maps have no lines. Where their destiny cannot find us.

Do not speak to me of what is practical. My love for you is the most impractical thing I have ever done. It has no place in this world they are building. So, we will make our own.

Come away with me.

Elias

There was no written reply to that last letter. Folks in the valley said that two shadows were seen moving north through Duggar Mountain just before dawn, one a farmer’s son who vanished from his bed, and the other, a quiet man who knew the songs of the rivers. They were never heard from again.

And I suppose the moral of it, if a story must have one, is that while empires and nations are busy with their grand and bloody destinies, the small, quiet destinies of the heart are often the ones that matter most. And sometimes, the truest act of defiance is not to fight a war, but simply to love, and to slip away into the woods, leaving the map-makers forever bewildered.

*****

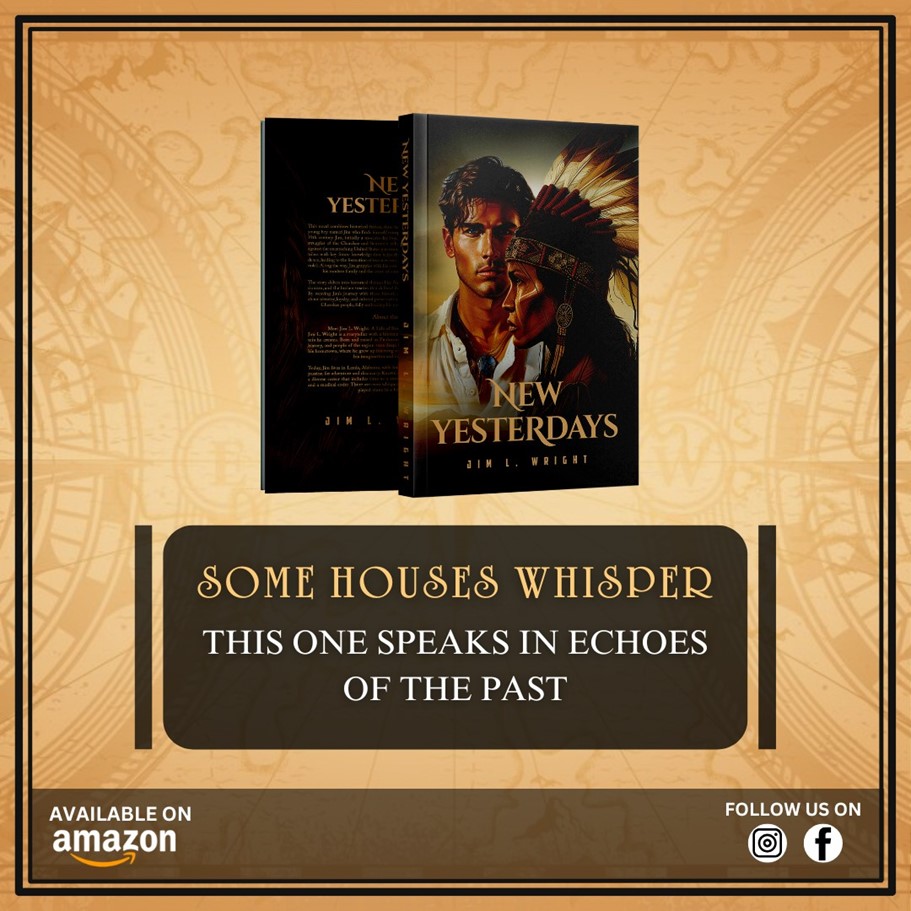

And, you know, I would never leave you while neglecting the obligatory shameless self-promotion. New Yesterdays is available through the following links: Books-A-Million, Barnes & Noble, and Amazon, as well as your favorite bookshops. The Audiobook is available from Libro.fm, as well as Amazon.

Captivating story, Jim!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Tim! Always good to hear from you!

LikeLiked by 1 person