Well, now, it so happens that in the town of Piedmont, Alabama, there was a feller by the name of Atticus Hunt. Atticus made his yearly living in the three weeks betwixt Thanksgiving and Christmas, operating a lot he called, with considerable optimism, “The Evergreen Emporium.” It was a fenced-off patch of mud and misery on the corner of Ladiga and Barlow, piled high with northern firs and pines that smelled powerful enough to cover the scent of damp cotton and desperation common to the season.

Atticus himself was a man whose face had been weathered by more Decembers than he cared to count, and he regarded his trees not with sentiment, but with the cold calculus of a Truckstop gambler sizing up a marked deck. He had his premium trees, tall and symmetrical as a Baptist deacon, which he called “The Patricians.” Then came the middling ones, a bit lopsided but still serviceable, “The Burghers.” And finally, down at the end, leaning against the splintery fence like a bunch of drunken sailors, was a collection of scrawny, needle-dropping misfits he privately referred to as “The Orphanage.”

It was a bitterly cold evening, the kind that bites at the tip of your nose and earlobes, and makes the wood smoke hang low over the town. Business had been slow, and Atticus was huddled over a pot-bellied stove in a shack that smelled of pine pitch and burnt coffee, contemplating the general foolishness of mankind and their holiday notions.

The door-harp twanged, a sorry little sound, and in shuffled a boy. He couldn’t have been more than ten, buttoned into a coat that was too thin and too short at the wrists, and his face had that pinched look that comes from more than just the cold. He didn’t look at the grand Patricians or the respectable Burghers. No, sir. His eyes, wide and serious, went straight to The Orphanage.

Atticus sighed, the steam from his breath adding to the general gloom. “Evenin’, son. Lookin’ for a tree for your Daddy?”

“No, sir,” the boy said, his voice quiet but steady. “For me and my Mama.”

He walked along the row of misfits with the concentration of a connoisseur. He passed by one that was as bald on one side as a mangy dog, and another that had a crook in its trunk you could hang a hat on. Finally, he stopped before the sorriest specimen in the whole lot. It was a tree that hadn’t so much grown as it had just given up early in life. It was scarcely three feet tall, its branches were sparse and uneven, and it had a kind of weary slump to it, as if it was tired of being a tree altogether.

“This’n,” the boy said, a note of finality in his voice.

Atticus leaned forward, his elbows on his knees. “Now, hold on, son. That ain’t a tree, that’s a botanical apology. Your Mama, she deserves one of these fine Patricians over here. I’ll make you a good price.”

The boy shook his head, his jaw set. “No, sir. This is the one.”

He dug into his pocket and pulled out a handful of change. It was a pitiful collection of pennies, a nickel, and two dimes, warm from his clutching. He held it out. “This is for the tree. And I got a nickel left for the stand.” He held up a single, solitary nickel.

Atticus looked from the boy’s earnest face to the handful of coins, and then to the wretched little tree. A smarter man, a harder man, would have taken the money and been glad to be rid of the eyesore. But Atticus Hunt, for all his grumbling, had a heart that hadn’t yet entirely petrified. He saw the whole story laid out before him plain as day: a proud mother, a boy trying to be the man of the house, and a budget thinner than charity soup.

He took the handful of change. It felt heavy, heavier than a gold ingot. “Well,” he grumbled, making a show of counting it. “Seems the price for this particular… ‘specimen’… has just come down. Considerably. This here covers the tree, and the stand is thrown in. Can’t have a tree fallin’ over, can we?”

The boy’s face lit up like a Christmas morning, which, in a manner of speaking, it was. He handed over the nickel for the stand with the gravity of a king sealing a treaty.

Atticus found a scrap of burlap and wrapped the tree’s root-ball, then tied the whole affair with twine. The boy hoisted it, his small frame staggering for a moment under the negligible weight.

“Thank you, mister,” he said, and he turned and marched out into the cold, a small boy carrying a small tree, both of them a little worse for wear but bound for a place where they would be appreciated.

Atticus stood in the doorway of his shack, watching him go. The wind had a mean bite to it, but he barely felt it. He looked down at the handful of change in his palm, then over at the empty spot where the pitiful tree had stood. He felt a peculiar sensation, a warmth that didn’t come from any stove.

He muttered to himself, “Confound it all,” and then, after a pause, “Merry Christmas, son.”

And it occurred to him then that he had just witnessed the first honest transaction of the whole season. That boy hadn’t bought a tree; he had bought a principle. And Atticus, the old river-rat, had sold a worthless tree and somehow come out richer for it. It just goes to show, the true value of a thing ain’t in its foliage or its symmetry, but in the peculiar and wonderful economy of the human heart.

*****

And, here, I’ll step out of the story to wish each and every one of you a very merry Christmas!

*****

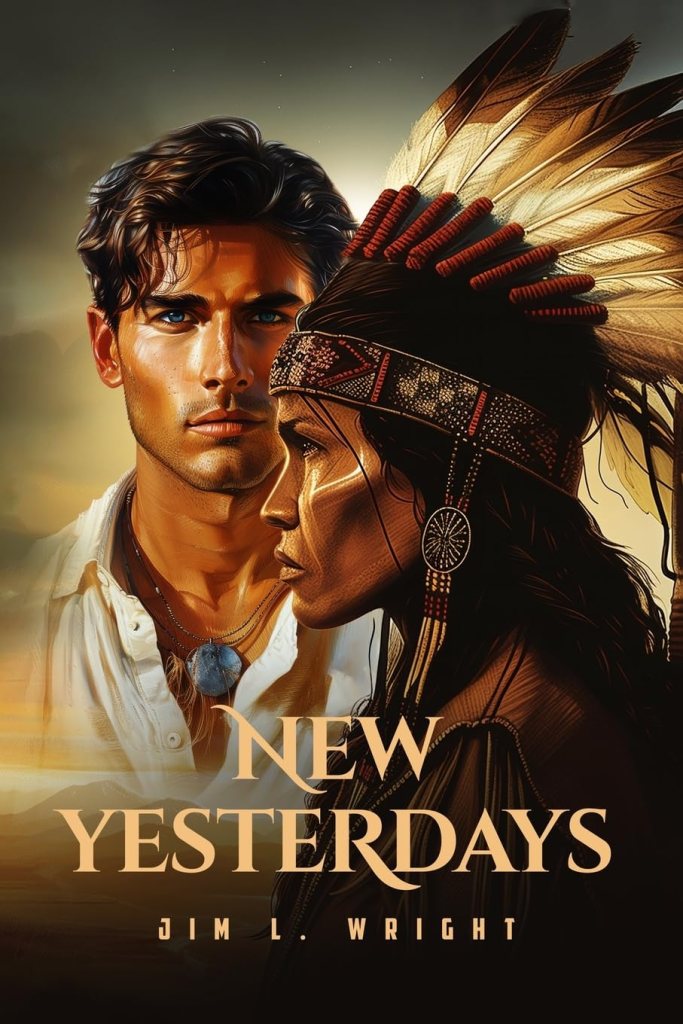

And, you know I couldn’t possibly neglect the obligatory shameless self-promotion. New Yesterdays, a very nice stocking stuffer, is available through the following links: Books-A-Million, Barnes & Noble, and Amazon as well as your favorite bookshops. The Audiobook is available from Libro.fm, as well as Amazon.

Your stories are fabulous, Jim. This is a great Christmas story that deserves to be told over and over.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aw, thank you so much, John!

LikeLiked by 1 person

😀

LikeLiked by 1 person