The feud between the Montagues and the Capulets was not a matter of politics or land to Tybalt. It was art. It was a sacred, violent dance, and he was its most devoted practitioner. He lived for the elegant arc of his rapier, the thrill of a well-placed insult, the simmering promise of a fight. The Montagues, to him, were clumsy, graceless oafs who sullied the purity of the quarrel.

Mercutio, kinsman to the Prince and friend by choice to Romeo, saw the whole affair as a colossal, tedious joke. He fought with words, with wit, with a dazzling, reckless energy that disarmed and infuriated in equal measure. He found Tybalt’s solemn devotion to the feud utterly absurd, a performance so self-serious it begged to be skewered.

Their first real meeting wasn’t with swords, but with words, in the sun-scorched marketplace. Tybalt, his hand already hovering near his hilt, had confronted Romeo. Mercutio had slithered between them, a grin splitting his face.

“What, drawn, and talk of peace? I hate the word, as I hate hell, all Montagues, and thee,” Tybalt had snarled.

“Tybalt, you rat-catcher, will you walk?” Mercutio had replied, his voice a melody of mockery. He wasn’t challenging him to a duel; he was inviting him to a dance of wits, a verbal duel where the sharpest weapon was a pun.

To Tybalt’s shock, he found himself disarmed. Not by a sword, but by a turn of phrase so clever, so audacious, it left him momentarily speechless. No one had ever met his fury with flirtation. No one had ever looked at his righteous anger and seen a game. He was unnerved, infuriated, and, to his horror, a little intrigued.

Their paths crossed again, a week later, at a masquerade. It was a Capulet feast, but Mercutio, ever the rule-breaker, had donned a simple mask of silver and slipped in. He saw Tybalt across the room, a dark, brooding figure in crimson, scowling at the dancers. On a whim, Mercutio approached.

“Dance with me, Prince of Cats,” he whispered, using the name he knew would sting. “Or are you afraid your gracefulness might be compromised by a commoner’s touch?”

Tybalt turned, ready to issue a challenge, but stopped. The mask obscured Mercutio’s face, but his voice, his maddening, confident voice, was unmistakable. “You,” he breathed.

“Me,” Mercutio confirmed, and without waiting for permission, took Tybalt’s hand. The touch was electric. Tybalt’s hand was calloused from practice, strong and firm. Mercutio’s was surprisingly gentle. As they moved through the steps of a pavane, a formal, stately dance, their eyes locked behind their masks. For the first time, Tybalt saw not a Montague’s jester, but a man whose eyes burned with a fire as intense as his own. And Mercutio saw not a humorless brute, but a man whose rigid posture hid a deep, simmering loneliness.

The dance ended, and without another word, they both slipped away into the garden, a silent, unspoken agreement hanging between them.

“Why do you do it?” Tybalt finally asked, his voice low. “Why do you mock everything I hold sacred?”

“Because it’s all so terribly serious,” Mercutio replied, leaning against a stone wall. “You’ve built this beautiful, intricate cage of honor and feud, and you march around inside it like it’s a palace. I just want to show you the door.”

“Perhaps I like the cage,” Tybalt shot back.

“Then you’re a fool,” Mercutio said softly. “A beautiful, passionate fool.”

And then, because the world was already mad, Mercutio leaned in and kissed him. It wasn’t a gentle kiss. It was a collision, a challenge, as sharp and sudden as a sword thrust. Tybalt, for a moment, was too stunned to react. He had expected insults, a challenge, a fight. He had not expected this. This was a different kind of duel; one he had no training for. But his instincts took over, and he kissed back, with a ferocity that surprised them both.

Their secret became a series of stolen moments. A rendezvous in the ruins of an old abbey, where Tybalt would practice his forms, and Mercutio would lie in the grass, offering acerbic commentary on his footwork. A shared bottle of wine in a secluded tavern, where they argued about poetry and honor until the sun came up. In the privacy of these moments, the feud dissolved. Tybalt learned to laugh at Mercutio’s jokes, and Mercutio learned to see the fierce, unwavering loyalty beneath Tybalt’s pride. They were two sides of the same coin, both defined by a passionate intensity, just expressed in different ways.

They knew they could never be open. Their love was a betrayal of everything their families stood for. So, they decided on a desperate, radical plan. They would marry in secret, not to unite the houses – that was a fool’s dream for star-crossed children – but to create their own world, a small, sacred space that belonged only to them.

They found an old Franciscan friar, a man more interested in the quiet poetry of the soul than the loud politics of Verona. He saw the desperate love in their eyes and agreed, seeing it not as a sin, but as a fragile miracle.

The ceremony was held at dawn in a small, crumbling chapel. There were no witnesses, no finery. Tybalt wore his simple leather tunic, and Mercutio was in his customary dark doublet. They spoke their vows in hushed tones, their hands clasped, the morning light filtering through the dusty stained-glass windows. When Friar Lawrence declared them husband and husband, the kiss that followed was not of challenge, but of profound, aching peace. They had forged their own truce, their own sacred bond.

An hour later, the world came crashing down. They were in the marketplace, the secret of their marriage a warm cloak around them, when Romeo, still high on his own secret wedding, appeared. Tybalt’s honor, his carefully constructed cage, reasserted itself. He could not let the insult of Romeo’s presence at the Capulet feast go. He had to maintain the facade.

“Romeo, the love I bear thee can afford no better term than this: thou art a villain.”

Mercutio’s blood ran cold. He saw the trap. Tybalt was performing for the crowd, for the name he bore. But he saw the flicker of desperation in his husband’s eyes. He was begging him to play along, to engage in their usual dance of insults and then walk away.

But Mercutio, in his love and his fury, could not let him fight Romeo alone. He drew his sword. “Tybalt, you rat-catcher, will you walk?”

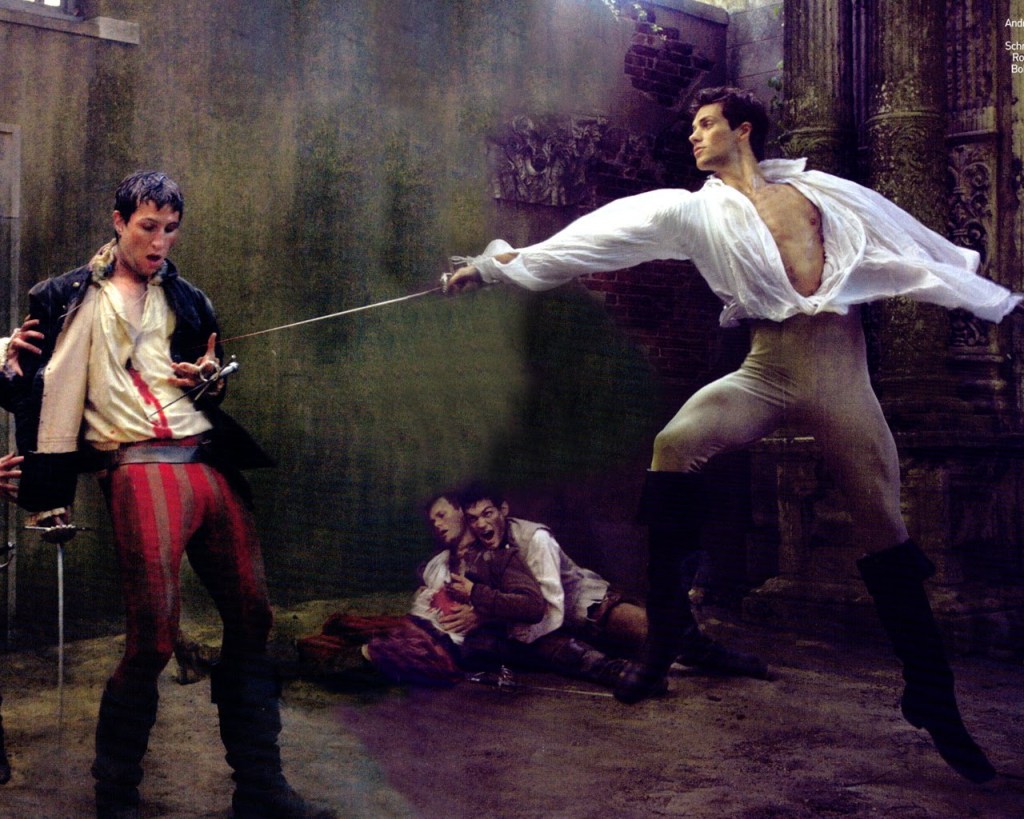

The fight was a blur of steel and rage, but it was different now. Every parry was a question, every feint a plea. They were not trying to kill each other; they were trying to break the spell, to force the other to yield, to drop the pretense. But the crowd was cheering, the die was cast. In a moment of chaos, as Romeo stepped between them, Tybalt’s sword found a gap. It was a mistake, a tragic miscalculation born of a performance he no longer believed in.

Mercutio staggered back, a look of profound betrayal on his face. He looked not at Romeo, who held him, but at Tybalt. He saw the horror dawning in his husband’s eyes.

“A plague o’ both your houses!” he gasped, the curse meant not for the Montagues and Capulets, but for the world that had forced them into this impossible dance. “They have made worms’ meat of me.”

He died in Romeo’s arms; his eyes locked on Tybalt across the square. In that moment, Tybalt’s world shattered. The art, the dance, the feud—it was all dust. All that was left was the man he loved, dead on the cobblestones by his own hand. He roared, a sound of pure, animal grief, and charged Romeo, not for honor, not for his name, but for a death wish.

He died a few moments later, his last thought not of his family’s honor, but of a silver mask and a secret kiss in a garden. The feud ended that day, not with a truce, but with the silent, unseen tragedy of two men who had loved each other so fiercely they were willing to marry in secret, and who were destroyed by the very performance they had tried to escape.

⁂

And, you know, with Christmas just around the corner, I shouldn’t neglect the obligatory shameless self-promotion. New Yesterdays, a very nice Christmas stocking stuffer, is available through the following links: Books-A-Million, Barnes & Noble, and Amazon as well as your favorite bookshops. The Audiobook is available from Libro.fm, as well as Amazon. Get yours today!

Captivating story, Jim!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Tim!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome, Jim. 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person